Mastering Abstract Concepts in AP Social Studies for Exam Success

AP Social Studies courses ask students to do something uniquely difficult: think with big,universalideas while working with very specific...

AP & Honors Mathematics

Explore Wiley titles to support both AP and Honors mathematics instruction.

Literacy Skills & Intensive Reading

Connections: Reading – Grades 6–12

Empower student success with a proven intensive reading program that develops strong reading skills in striving readers.

Drama, Speech & Debate

Basic Drama Projects 10th Edition

Build students’ confidence and competence with comprehensive, project-based theatre instruction.

Literature

Connections: Literature

Support learners as they study dynamic, relevant texts and bring the richness of diverse voices to students through literature.

Literature & Thought

Develop critical thinking, reading, and writing across literacy themes, genres, historical eras, and current events.

Language Arts

Vocabu-Lit® – Grades 6–12

Help students build word power using high-quality contemporary and classic literature, nonfiction, essays, and more.

Connections: Writing & Language

Help students develop grammar, usage, mechanics, vocabulary, spelling, and writing and editing skills.

Reading/English Language Arts

Measuring Up to the English Language Arts Standards

Incorporate standards-driven teaching strategies to complement your ELA curriculum.

English Language Learners

Measuring Up for English Language Learners

Incorporate research-based best practices for ELLs with an approach that includes a focus on language acquisition strategies.

Mathematics

Measuring Up to the Mathematics Standards

Incorporate standards-driven teaching strategies to complement your mathematics curriculum.

Foundations

Measuring Up Foundations

Help students master foundational math skills that are critical for students to find academic success.

Science

Measuring Up to the Next Generation Science Standards

Give students comprehensive NGSS coverage while targeting instruction and providing rigorous standards practice.

Assessment

Measuring Up Live

Deliver innovative assessment and practice technology designed to offer data-driven instructional support.

For a better website experience, please confirm you are in:

3 min read

Perfection Learning Dec 22, 2025 9:11:49 AM

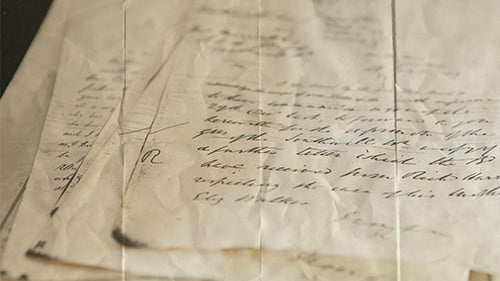

Primary sources provide students with a personal window into the past, enabling them to view history as human stories rather than a list of facts. They also strengthen critical thinking as students question authors, audiences, and purposes instead of passively accepting a single narrative.

For AP Social Studies, this is not optional: success on SAQs, DBQs, and LEQs depends on sourcing, contextualization, and argumentation grounded in evidence, all of which develop from sustained work with documents.

Traditional close reading often means heavy annotation and a series of comprehension questions that can quickly become tedious. To move beyond that, shift from “What does this document say?” to “What can we do with this document?”

Some key moves include:

Prioritize sourcing and perspective before content, asking who created the source, for whom, why, and with what bias.

Build in comparison, corroboration, and contradiction between sources so students practice thinking like historians rather than like test-takers.

Slow down with fewer documents and more time for discussion, writing, and reflection to deepen understanding instead of racing through packets.

Here are classroom-ready ways to make primary sources active, collaborative, and memorable.

Turn a document set into a puzzle students must solve.

Give students a small set of related sources (image, short text, chart) without full context and have them infer what is happening, who is involved, and why it matters.

Require them to support each inference with specific evidence from the documents, mirroring the kind of reasoning AP expects on DBQs.

How AMSCO helps: AMSCO AP U.S. History, AP World History, and AP European History titles embed document sets and stimulus-based questions that naturally lend themselves to this “history lab” approach, since students must interpret charts, maps, and excerpts to answer AP-style multiple-choice and SAQs.

Primary sources are ideal prompts for students to step into historical roles and grapple with conflicting viewpoints.

Assign each student or group a source and have them “become” its author, then stage a town-hall, salon, or debate where they argue from that perspective.

Ask students to write short speeches, diary entries, or letters composed in the voice of the creator, citing lines from the original text to justify their choices.

How AMSCO helps: AMSCO chapters often juxtapose contrasting voices—such as reformers and opponents, imperial powers and colonized peoples—alongside guiding questions, making it easy to turn those into perspective-based debates or structured academic conversations.

Students often connect more readily to images, graphics, and political cartoons than dense text alone.

Use “See–Think–Wonder” or similar strategies with photographs, maps, and cartoons to slow students down and push them from observation to interpretation.

Pair a short written source with a related visual and have students explain how the two reinforce or challenge each other, supporting claims with evidence from both.

How AMSCO helps: AMSCO programs frequently incorporate political cartoons, graphs, timelines, and maps tied directly to unit content and skill-based questions, allowing students to practice the same integrative analysis they will see on AP exams.

Stations turn document analysis into a movement- and talk-rich activity rather than a solitary task.

Set up stations around the room with different types of sources: a speech excerpt, a chart, a cartoon, a letter, etc.

Have groups rotate, adding annotations, questions, or claims at each station, then synthesize what they learned into a timeline, cause-and-effect chain, or argument.

How AMSCO helps: Because AMSCO units offer multiple stimulus types and AP-style questions aligned to each topic, teachers can easily break these into station tasks, with each station focusing on a different historical thinking skill or reasoning process.

Giving students creative tasks anchored in evidence keeps the rigor while boosting engagement.

Invite students to construct a narrative (short story, diary sequence, or storyboard) grounded in a cluster of primary sources, requiring direct quotations or references as proof.

Use strategies such as continuum lines (“most democratic” to “least democratic” documents) or “primary source sandwiches” (brief context, document excerpt, student explanation) to scaffold argument development.

How AMSCO helps: AMSCO’s chapter and unit assessments include DBQ-style prompts, short-answer questions, and long-essay prompts, which can be converted into “mini-DBQs” where students first complete a creative product, then revise it into AP-formatted writing using the same evidence.

Perfection Learning’s AMSCO AP Social Studies materials are intentionally structured around the skills that primary sources develop and AP exams assess.

Key ways these resources support your instruction include:

Systematic skill scaffolding: AMSCO texts incorporate sourcing, contextualization, comparison, and causation throughout each unit, gradually increasing document complexity and task demands to match AP expectations.

Abundant practice with exam-style items: Stimulus-based multiple-choice questions, SAQs, DBQs, and LEQs built around primary and secondary sources provide practice with the same formats students will encounter on test day.

Flexible use with your own activities: Because every AP-aligned unit is rich in concise overviews, key concepts, and integrated source sets, teachers can easily repurpose AMSCO passages and visuals into the mystery labs, debates, stations, and creative tasks described above.

By deliberately pairing these kinds of engaging strategies with AMSCO’s structured AP skill progression, AP Social Studies teachers can turn primary-source work into a powerful engine for both deeper historical understanding and stronger exam performance.

AP Social Studies courses ask students to do something uniquely difficult: think with big,universalideas while working with very specific...

For many students, the most intimidating part of an AP® Social Studies exam isn’t the content—it’s the rubric.

When most teachers—and students—think about a DBQ, they think about writing. And yes, writing the full essay is essential. But if that’s all we ever...

Unlock the power of historical thinking and writing as you elevate complexity and engagement in AP History classrooms. Presented by experienced AP...

Join AP experts Brandon Abdon, Colin Baker, and Bob Topping to discover scaffolded approaches to teaching the APUSH, AP Euro, and AP World History...

This interactive webinar focuses on scaffolded approaches to the finishing touches necessary for higher-level success on the LEQ and DBQ portions of...

One of the best days I’ve ever had in the classroom is when we look at art.

Experienced AP World History teacher Dave Drzonek and AP World History Exam table leader Charlie Hart discuss what students did well and what they...

Cultural diffusion and cultural syncretism are two important concepts in the AP® World History curriculum. Because of its importance, I’ve developed...

In celebration of Women's History Month, explore this lesson with your students that gives them the opportunity to practice an important part of the...

As we get closer to the AP® World History Exam, students will begin to stress about the required essays they will write as part of the exam. The...

The teaching of AP® World History can be a daunting task at times. Teachers are asked to teach over 800 years of historical content and then develop...